Sat Jul 05 10:15:26 PM +08 2025#72

hehe

hehe

IBM Selectric I

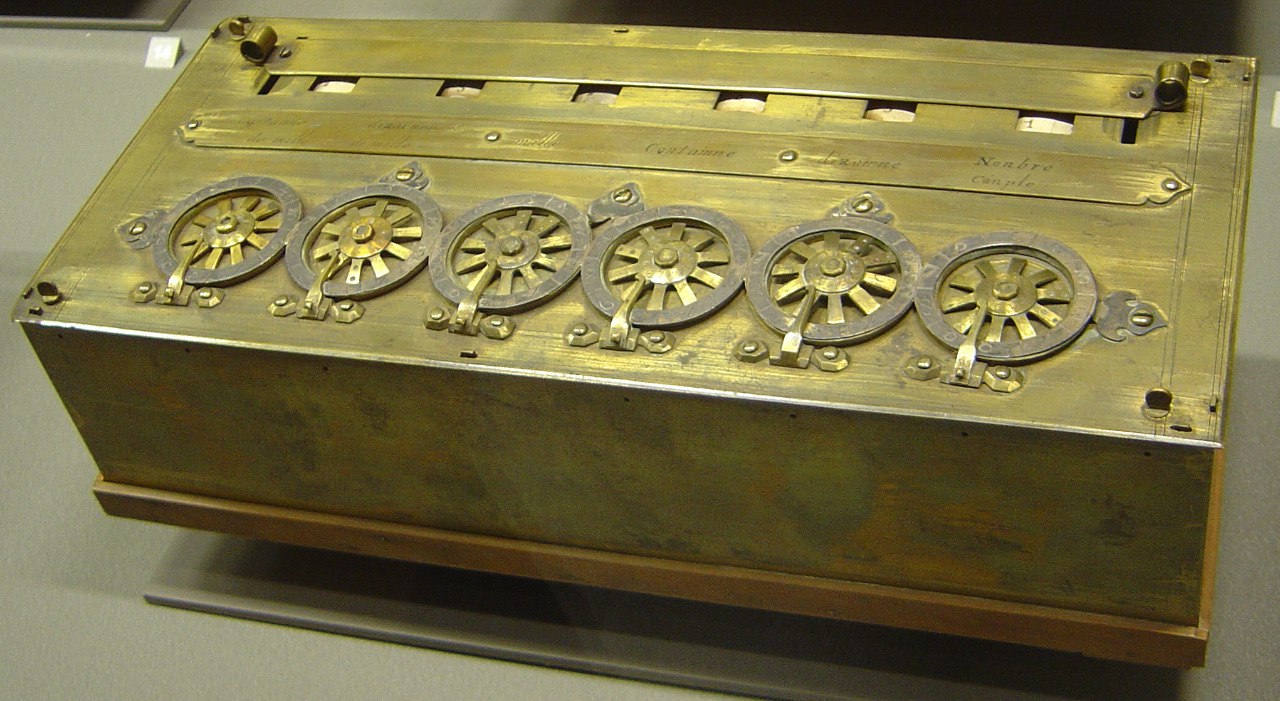

Arts_et_Metiers_Pascaline_dsc03869.jpg

DEC Digital VT100

Connection Machine (1985)

The idea of balancing a search tree is due to Adel’son-Vel’skiĭ and Landis, who introduced a class of balanced search trees called AVL trees in 1962. Another class of search trees, called 2-3 trees, was introduced by J. E. Hopcroft in 1970. A 2-3 tree maintains balance by manipulating the degrees of nodes in the tree. Bayer and McCreight later generalized 2-3 trees to form B-trees. Red-black trees were invented by Bayer under the name symmetric binary B-trees. Guibas and Sedgewick studied their properties in detail and introduced the red/black color convention. Andersson proposed a simpler-to-code variant of red-black trees, which Weiss later called AA-trees. An AA-tree is similar to a red-black tree except that left children may never be red. Treaps were proposed by Seidel and Aragon. They became the default implementation of a dictionary in LEDA, a well-known collection of data structures and algorithms. Other variations on balanced binary trees include weight-balanced trees, k-neighbor trees, and scapegoat trees. One of the most intriguing is the splay tree introduced by Sleator and Tarjan, which is self-adjusting. Splay trees maintain balance without any explicit balance conditions. Instead, splay operations involving rotations are performed within the tree every time an access is made. The amortized cost of each operation on an n-node tree is logarithmic. Skip lists provide an alternative to balanced binary trees. A skip list is a linked list augmented with additional pointers, allowing dictionary operations to run in expected logarithmic time.

reasonable

Lana_Del_Rey_Cannes_2012.jpg Elizabeth Woolridge Grant

macro_rules! box_it {

($value:literal) => {

Box::new($value)

};

}

fn main() {

let stuff = box_it!("hello, world");

println!("{stuff:?}");

}

fn main() {

println!("hello, world");

}

N.Wirth. Algorithms and Data Structures. Oberon version Harold Abelson, Gerald Jay Sussman, Julie Sussman. Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs

ken-and-den.jpeg

«Мы постоянно меняемся и очень важно помнить о том, что ты был положительным персонажем» Бараш

First, we want to establish the idea that a computer language is not just a way of getting a computer to perform operations but rather that it is a novel formal medium for expressing ideas about methodology. Thus, programs must be written for people to read, and only incidentally for machines to execute. Second, we believe that the essential material to be addressed by a subject at this level is not the syntax of particular programming-language constructs, nor clever algorithms for computing particular functions efficiently, nor even the mathematical analysis of algorithms and the foundations of computing, but rather the techniques used to control the intellectual complexity of large software systems.

Start ridiculously small (a single pushup or one minute of meditation) Attach new behaviors to existing routines (meditate after brushing teeth) Celebrate immediate small wins to reinforce the behavior Focus on consistency rather than perfection Design your environment to make good habits easier and bad habits harder

Cultivating positive habits provides a powerful mechanism for life improvement. Regular exercise represents a classic example—initially challenging to establish but relatively easy to maintain once integrated into your routine. This principle applies equally to reading, writing, meditation, or other beneficial practices. With exercise specifically, I personally reject the concept of scheduled rest days because they tend to multiply into extended inactivity periods. Instead, I find daily movement more sustainable, even if it’s minimal, adjusting intensity according to energy levels and recovery needs.

This book is dedicated, in respect and admiration, to the spirit that lives in the computer. ``I think that it's extraordinarily important that we in computer science keep fun in computing. When it started out, it was an awful lot of fun. Of course, the paying customers got shafted every now and then, and after a while we began to take their complaints seriously. We began to feel as if we really were responsible for the successful, error-free perfect use of these machines. I don't think we are. I think we're responsible for stretching them, setting them off in new directions, and keeping fun in the house. I hope the field of computer science never loses its sense of fun. Above all, I hope we don't become missionaries. Don't feel as if you're Bible salesmen. The world has too many of those already. What you know about computing other people will learn. Don't feel as if the key to successful computing is only in your hands. What's in your hands, I think and hope, is intelligence: the ability to see the machine as more than when you were first led up to it, that you can make it more.'' Alan J. Perlis (April 1, 1922-February 7, 1990)

Wega

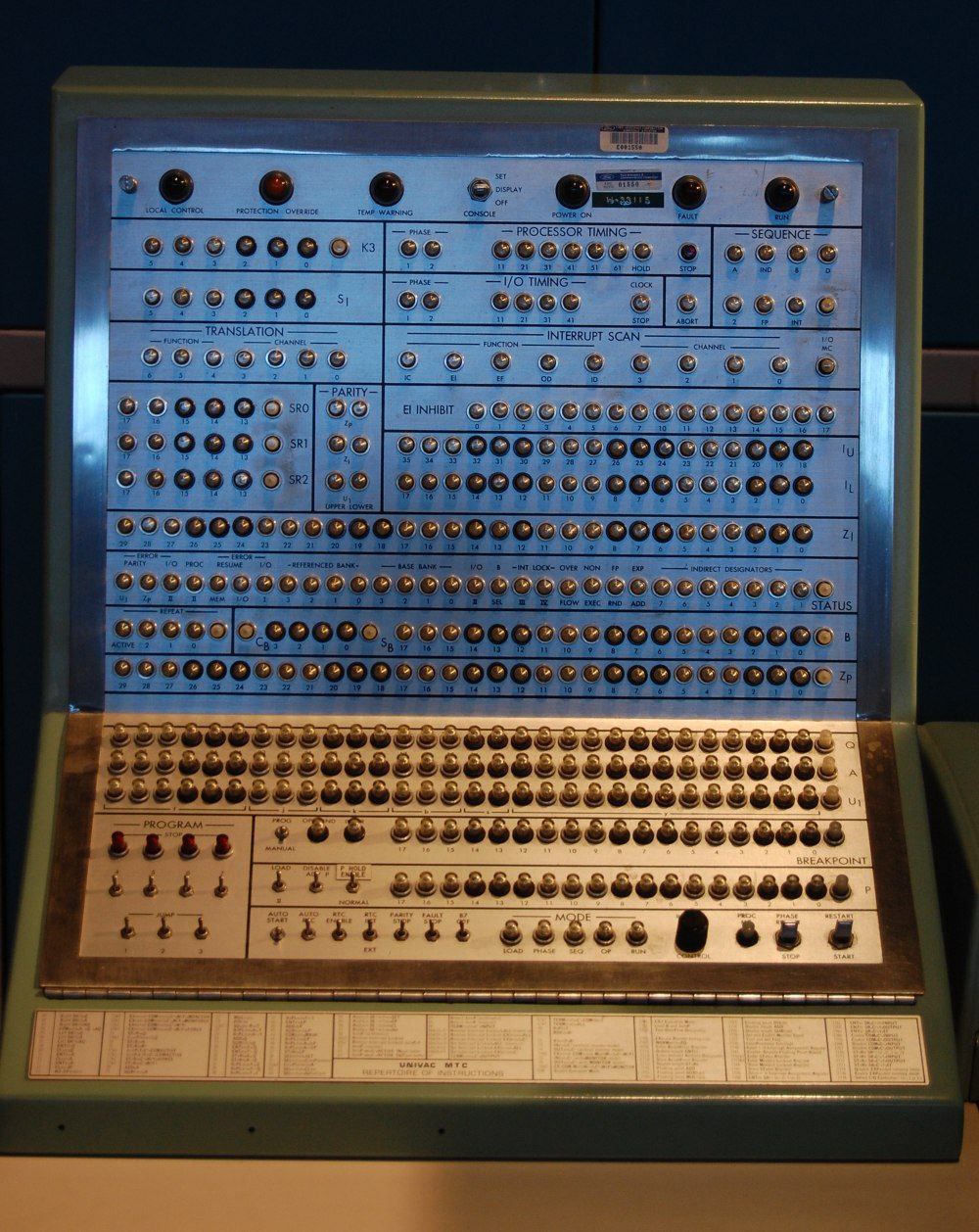

IBM System/360

Embrace object-oriented patterns for organization. For organizing larger parts of your application, consider object-oriented constructs. Using structs or enums can encapsulate related data and functions, providing a clear structure without worrying about the details. Leverage functional patterns for data transformations. Especially within smaller scopes like functions and closures, functional methods such as mapping, filtering, or reducing can make your code both concise and clear. Use functional programming when you can phrase your problem as a series of transformations over some data.} Use imperative style for granular control. In scenarios where you’re working close to the hardware, or when you need explicit step-by-step execution, the imperative style is often a necessity. It allows for precise control over operations, especially with mutable data. This style can be particularly useful in performance-critical sections or when interfacing with external systems where exact sequencing matters. However, always weigh its performance gains against potential readability trade-offs. If possible, encapsulate imperative code within a limited scope. Prioritize readability and maintainability. Regardless of your chosen paradigm, always write code that’s straightforward and easy to maintain. It benefits not only your future self, but also your colleagues who might work on the same codebase. Avoid premature optimization. Don’t prematurely optimize for performance at the cost of readability. The real bottleneck might be elsewhere. Measure first, then optimize. Elegant solutions can be turned into fast ones, but the reverse is not always true.